By Dr David McCollum, University of St Andrews

Working From Home (WFH), whether on a partial (hybrid) or full-time (remote) basis, increased dramatically with the onset of the covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and has remained widespread since. One of the many shifts that these changes in working practices have potentially endangered is in relation to spatial inequalities. The UK is one of the most regionally unequal of all higher income countries in terms of the geographical distribution of wealth, productivity and skills. However, might WFH led to the redistribution of high skill workers and economic activity from overheating property markets, primarily in London and the South East of England, to other relatively affordable parts of the country, thus producing a more equitable distribution of human capital and productive economic activity? After all, why would people who can work from home elect to reside in big and expensive cities when they can live in more affordable, spacious and aesthetically appealing locales elsewhere?

Recently conducted research by the geographer Dr David McCollum at the University of St Andrews suggests that WFH is regrettably unlikely to be a game changer for spatial inequalities. This is because (a) WFH is concentrated amongst graduates and those in professional and managerial jobs, who tend to be concentrated in the more prosperous parts of the country and (b) hybrid working is much more common than fully remote working, meaning that skilled workers still must reside within a commutable distance of the big cities which offer the best opportunities for career progression.

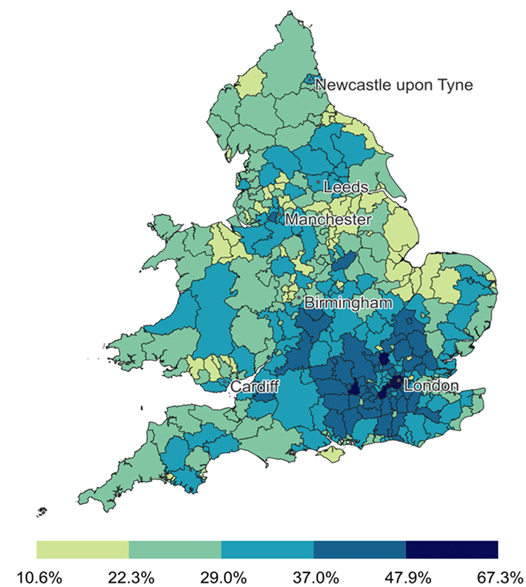

There is good statistical data on the geography of WFH during the pandemic, but there remains uncertainty regarding its spatial patterning post-pandemic. The national Census, conducted every ten years, is the most robust source of data on this topic. In total 8.7 million (31.2%) usual residents aged 16 years and over in employment in England and Wales worked mainly at or from home in the week before Census Day, 21st March 2021. The map below based on the census data illustrates the distinctive geography of WFH. Whilst over two-fifths of workers in London (42.1%) did this, the equivalent figure in the North East was only one-quarter (24.8%).

The top local authorities for WFH were concentrated in and around London (usually more than half of the workforce) whereas it was least prevalent in eastern coastal areas between the Humber estuary and the Wash (less than a fifth of workers). WFH was most prevalent in the City of London (67.3%) and least common in Boston, Lincolnshire (10.6%). Only two areas north of the classic north-south divide sit within the top 50 areas for WFH (Rushcliffe and Trafford). Statistical analysis at the local authority level shows that WFH propensity is closely correlated with share of workforce in professional and managerial jobs, qualification level, property values, pay rates and deprivation levels. The significant caveat is that these insights relate to the covid rather than post-covid period. For this reason, Dr McCollum engaged with key regional and local stakeholders in WFH ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ spots to gauge how WFH was playing out on the ground post-pandemic and what its geographical implications might be.

Key findings to emerge from the qualitative aspect of the research indicate that changes in working practices brought about by the pandemic have most likely reflected and reinforced existing social and spatial inequalities rather than transformed them. This is because post-pandemic, WFH remains commonplace, but hybrid working is much more prevalent than fully remote working. This has implications for the distribution of human capital, as most high skill workers must still reside within a reasonable commuting distance of the larger and buoyant labour markets which offer the best pay, conditions and opportunities for progression. WFH has thus created donut effects around big cities, in that those at well-established stages of their careers are able to relocate further away from their place of work. This results in less frequent but longer commutes. This is therefore likely to mean an ongoing resilience of the core-periphery economic geography model.

That said, an emphasis on place attractiveness could become increasingly important as more footloose hybrid workers increasingly base their residential preferences on place amenities rather than closeness to place of work. The cultural offer that places can make will be key to attracting and retaining the skilled and qualified workers that have most choice regarding residential location. This place attractiveness agenda could include investment in improving the aesthetics of places and their cultural ‘vibe’ and ‘offers’.

However it should be noted that the relationship between attracting those who can WFH to an area and the wider principles of achieving balanced and inclusive growth remains uncertain. As such, there is scope for research that increases understanding of the relationship between remote-hybrid working in an area and socio-economic indicators such as productivity and wage and employment growth.

Another pertinent question relates to the longer-term trajectory of the geography of employment and home relations and their associated consequences for post-pandemic worlds of work. Might employers increasingly mandate that employees ‘return to the office’? Will migrating to the largest and best performing cities remain an important catalyst for career development for younger workers in particular sectors? Will the ongoing rise of longer-distance commuting result in more spatially elongated travel-to-work areas? In time, further research will be able to help address these key questions. For example, the next wave of the UK Household Longitudinal Study will be available in November 2025. This will present scholars with a sufficiently large enough sample size to better assess the relationship between WFH and residential mobilities in the post-pandemic context.

About the author: Dr David McCollum is a Senior Lecturer in Geography at the University of St Andrews and a member the ESRC Centre for Population Change. David’s research interests include the welfare state, labour market change and labour migration.

Suggested further reading

Bissell, D., Crovara, E., Gorman-Murray, A. & Straughan, E. (2025) What does it mean to be present at work? Negotiating attention, distraction and presence in working from home. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.70000

Cockayne, D. & Treleaven, C. (2023) Autonomy and control in the (home) office: Finance professionals’ attitudes toward working from home in Canada as a result of COVID-19 lockdowns. Area. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12897

McCollum, D. (2025) Post-pandemic geographies of working from home: More of the same for spatial inequalities? Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12749

How to Cite

McCollum, D. (2025, March) Post-pandemic geographies of working from home: more of the same for spatial inequalities? Geography Directions. https://doi.org/10.55203/DIYZ6244