By Duaa Sameer, Karachi Urban Lab, Bosibori Barake, Kounkuey Design Initative, and Muhammad Arsam, Karachi Urban Lab

Life in mega-cities is always riddled with cycles of risks and uncertainties that challenge Ash Amin’s (2006) conception of ‘the good life’ – a set of four principles that Amin terms essential to making life in cities tenable. With Karachi, Pakistan and Nairobi, Kenya experiencing intensified bouts of heatwaves and floods, along with accelerated housing and commercial development, state policy across both countries remains inadequate in addressing social challenges and the threats to health and well-being faced by marginalised communities.

Inequality, climate change and urban risks

Karachi and Nairobi are highly unequal cities with roughly 62% of their populations living on 9% and 5% of their urban land, respectively (Anwar et. al, 2021; Ono & Kidokoro, 2020). These informal settlements are not only some of the most densely populated in the world, but also have materially fragile housing with subpar access to basic amenities, and are thus extremely vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

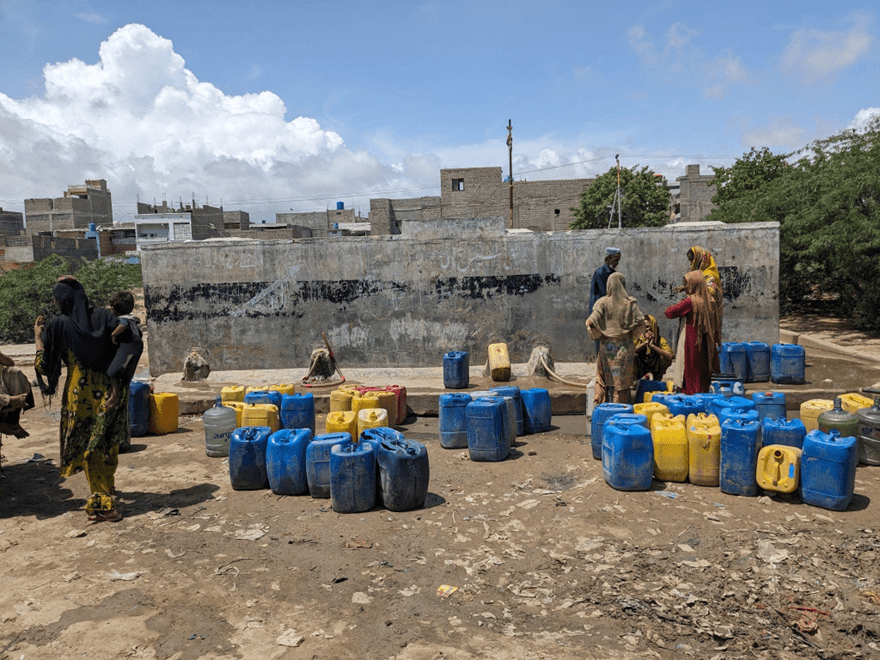

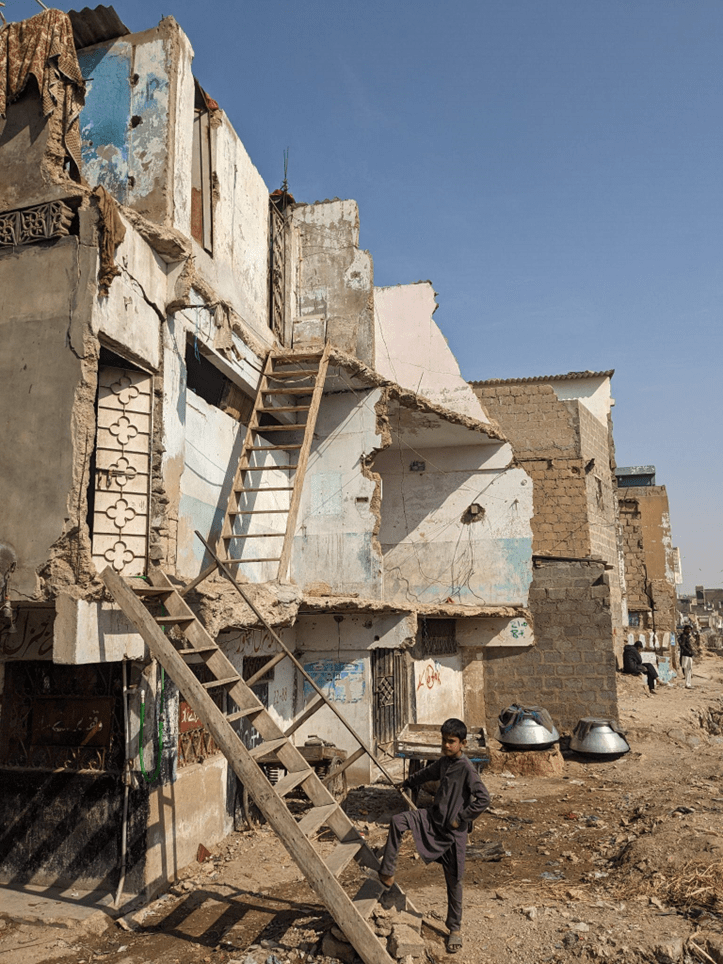

In Karachi’s informal settlements, access to infrastructural services like electricity, water, cooking gas, and health has degraded over time. Additionally, informal settlements along Karachi’s stormwater channels have faced incessant demolitions since 2020 to make way for an urban flood mitigation project. In Nairobi, the informal settlements of Mukuru, Vumilia and Kibera lie alongside three fairly new road development projects, the Nairobi Expressway, Outer Ring Road and the Missing Link Road. The implementation of these road projects has caused significant disruption to life – homes and livelihoods have been displaced, social networks have been severed, and economic hardship has become rife. While these disruptions are a daily occurrence for the residents in informal settlements, representing one aspect of the urban violence they face, such daily risks are being exacerbated by increasing occurrences of climatic events like rains, floods, and heatwaves.

Our research shows how urban violence and climate risk are not isolated phenomena, but are deeply intertwined and intensify each other. We understand urban violence as harm that is brought upon individual and communal life as a consequence of infrastructural disrepair and inadequate planning policies. Risk, a consequence of urban violence and severe climatic events, accumulates spatially, temporally, and is linked to social identity. For example, in urban informal settlements, when partially demolished concrete houses and tin-shacks heat up every day and flood every year, not only are material possessions destroyed, but the men, women, and children who reside there get sick, injured, and even die.

The work of maintenance and repair in cities is risk-laden labour that is performed unevenly by individuals and communities. Fragile housing in informal settlements requires daily maintenance: cotton and plastic tents degrade, wood needs to be scavenged to fire stoves, water needs to be fetched, and electricity needs to be procured. In South Asia and Africa, this labour of repair and care is also deeply gendered, which means women face greater risks as they carry out these daily responsibilities. In Sindhabad, a tent settlement of long-term climate migrants on the outskirts of Karachi, women will sometimes need to cross the highway to fetch water, a task that exposes them to the risk of fatal accidents. In essence, poor women in informal settlements face the double onslaught of urban violence and rapidly accelerating climate risks in the form of extreme heat, rains, storms, and flooding.

Using this understanding of urban risk as everyday, dynamic, compounding, and gendered, our Building Infrastructures of Climate Repair (BICR) team asks, how is well-being in cities repaired and maintained in the face of climate change? Given the complexity of whose vulnerabilities are heightened in the face of urban and climate risks, we ask what ‘pro-poor and gender sensitive’ rehabilitation might look like in these two cities. Our research explores what adaptation looks like on the personal and communal level, how it is performed, and how policy can comprehend contextually-specific risk interactions with gender, season, and locality to enable meaningful adaptation interventions. This concerns the emancipatory potential of the project, that is, the ways in which policy must begin seeing the nature of urban climate risks, how they operate and are managed by low-income populations in order to remedy existing marginalisation.

Thinking for policy: Emancipatory possibilities of climate repair

We see the emancipatory possibilities of our work in three ways. First, poor urban planning processes place climate-displaced people in a state of standby – one where communal, economic, social ties are severed, and maintenance and repair of well-being is curtailed. ‘Climate repair’ infrastructures need not only be major developmental projects; rather, they should encompass physical and social networks. This should ultimately develop into local networks of cooperation and leadership, and practices of everyday collaborative living, through which adaptations to new risks are enacted and residents’ daily well-being is maintained.

Second, displacement, as a consequence of major urban developments and climate disasters, ruptures social bonds in communities where health, well-being, and financial security are joint endeavours connected to land. When people are uprooted, communal forms of ensuring food and financial security, as well as health, take a direct hit as families are scattered. This fragmentation compounds urban risks in previously tight-knit communities. We advocate for these human costs of development to be considered in policy conversations to present a more comprehensive picture of what post-disaster losses look like beyond just monetary calculations.

Third, we see urban risks as non-static, and as capable of evolving on a day-to-day basis, especially in new informal settlements of climate migrants in cities. Life in these settlements is made up of fragile arrangements that require daily upkeep and remain at constant threat of breakdown. There is an emancipatory potential in understanding the changing, cascading and compounding features of risk as a necessary requisite for an adequate policy response.

As we see a global increase in the frequency and severity of climate disasters, especially floods and heatwaves, we must start seeing the urban climate risks that emerge from them in all their complexity. For us, these new urban risks deserve serious consideration for two reasons. First, climate disasters hit the most impoverished sections of urban populations, e.g. people living in fragile housing, the hardest. It was no coincidence that during the 2015 heatwave in Karachi, 750 of the total 1200 who died as a result lived in the city’s poorest areas. Similarly, partial or complete destruction of tent and tin houses by flooding causes lasting damage to a community’s physical infrastructure and built environment, increasing the likelihood of illness and injury from unsafe infrastructure while reducing access to amenities like water and electricity at the same time. Second, even within marginalised communities, the experience of urban climate risks differs across the lines of gender and age. It becomes very important to consider who is most at risk, especially when the responsibilities of household maintenance are performed by women and supported by children, making their exposure to heat, floods, storms, and fires that much greater.

Our work in Pakistan and Kenya shows us that planning policies will need to consider the complex interlinkages of these new urban climate risks and who they make vulnerable in order to enable meaningful adaptation work.

About the authors: Duaa Sameer is a Research Associate at Karachi Urban Lab, Bosibori Barake is a Planning Associate at Kounkuey Design Initiative, and Muhammad Arsam is a Senior Research Associate at Karachi Urban Lab.

Suggested Further Reading

Cheung, T.T.T. & Fuller, S. (2022). Rethinking the potential of collaboration for urban climate governance: The case of Hong Kong. Area. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12781

De Sherbinin, A., Schiller, A., & Pulsipher, A. (2007). The vulnerability of global cities to climate hazards. Environment and Urbanization. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247807076725

Enarson, E., Fothergill, A., Peek, L. (2007). Gender and Disaster: Foundations and Directions. In: Handbook of Disaster Research. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-32353-4_8

Garcia, A. & Tschakert, P. (2022). Intersectional subjectivities and climate change adaptation: An attentive analytical approach for examining power, emancipatory processes, and transformation. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12529

Singh, D. (2020). Gender relations, urban flooding, and the lived experiences of women in informal urban spaces. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies. Available at: 10.1080/12259276.2020.1817263

Tulumello, S. (2018, December 13). What is urban violence? Progress in Political Economy. Available at: https://www.ppesydney.net/what-is-urban-violence/

How To Cite

Sameer, D., Barake, B., Arsam, M. (2023, 27 November) Exploring urban risk, climate change and the emancipatory possibilities of climate repair infrastructures in Karachi and Nairobi. Geography Directions. https://doi.org/10.55203/ISSE5621